Here are some facts about Roman Chariots in ancient Rome / chariot racing in ancient Rome:

Design of ancient Roman chariots

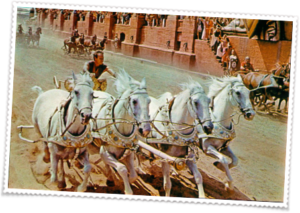

Roman racing chariots were designed to be as small and lightweight as possible. Unlike military chariots, which were larger and often reinforced with metal, racing chariots were made of wood and afforded little support or protection for the charioteer, who basically had to balance himself on the axle as he drove.

The ancient Romans loved chariot racing. In early Roman times, young nobles used to race their Roman Chariots around the 7 hills of Rome. People had to scatter to get out of the way.

Roman Chariots drawn by two horses were called “bigae” and those drawn by four horses “quadrigae”. “Triage”, “Sejuges” and “Septemjuges” (three, six and seven horses) were less usual but not unknown.

Chariot Races in Ancient Rome

Possibly the oldest spectacular sport in Rome, chariot racing dates back at least to the sixth century BCE. It was quite popular among the Etruscans, an advanced civilization of non-Italic people who for a time dominated the area around Rome and contributed greatly to many aspects of Roman civilization.

Location of chariot races in ancient Rome

Ancient Roman chariot races were held in the Circus, such as the Circus Maximus. The original Circus Maximus was built out of wood. It burnt down a couple of times. During the Roman Empire, the Circus Maximus was rebuilt using marble and concrete.

The festivities such as the Ludi Magni which were celebrated with the chariot races in honor of Jupiter generally began early in the morning with a religious procession called the “Pompa Circensis”. The full race was called a “missus” and generally included seven laps (called “curricula”) around the end posts called “metal”.

Winning ceremony for ancient Roman the Chariot Race

When the race was finally over, the presiding magistrate ceremoniously presented the victorious charioteer with a palm branch and a wreath while the crowds cheered wildly; the more substantial monetary awards for stable and driver would be presented later.

This terracotta lamp shows a victorious charioteer processing in the Circus Maximus; he holds a palm branch and prize wreath, and one can see the spine behind him with the dolphins for counting laps, the obelisk, and a shrine to a deity.

Apart from achieving love, glory and laurel crowns in the manner of Greece, the winning charioteers could make quite a monetary fortune. Reaching success would probably mean having your portrait scribbled all over the walls of the city.

Each race could have huge monetary prizes and successful riders could become the Roman equivalent of millionaires. Chariot racers tended to be slaves but this didn’t prevent them from amassing huge fortunes and redeeming their freedom.